Can you tell us a bit about the selected exhibiting galleries?

In Bawwaba 2020, we have 10 solo artistic presentations from wonderfully diverse galleries – Vermelho (Sao Paulo), Vadehra Gallery (Delhi), Canvas Gallery (Karachi), Vin Gallery (Ho Chi Minh City), Galleria Giampaolo Abbondio (Milan), Nature Morte (Delhi), Galerie Peter Sillem (Frankfurt), Revolver (Peru), Blueprint 12 (Delhi) and Saradipour Art Gallery (Los Angeles). I see these galleries as observatories or weather stations, their antennae finely attuned to seeking out practices at the leading edge of artistic inquiry and formal experiment.

In my selection of the artists, I was alert to the instinctual and sensuous provocations of form as well as to the way in which micro-narratives relayed larger histories in compressed form. I responded to the presence of dust, skin, light, the space between land and sea, the unending journey, the tormented earth with its heart torn open. One of the emergent foci of Bawwaba 2020 is the landscape sedimented with the memory of humankind but also the cumulative memory of the elements. Another focus is the productive interplay between archive and materiality, research and fiction.

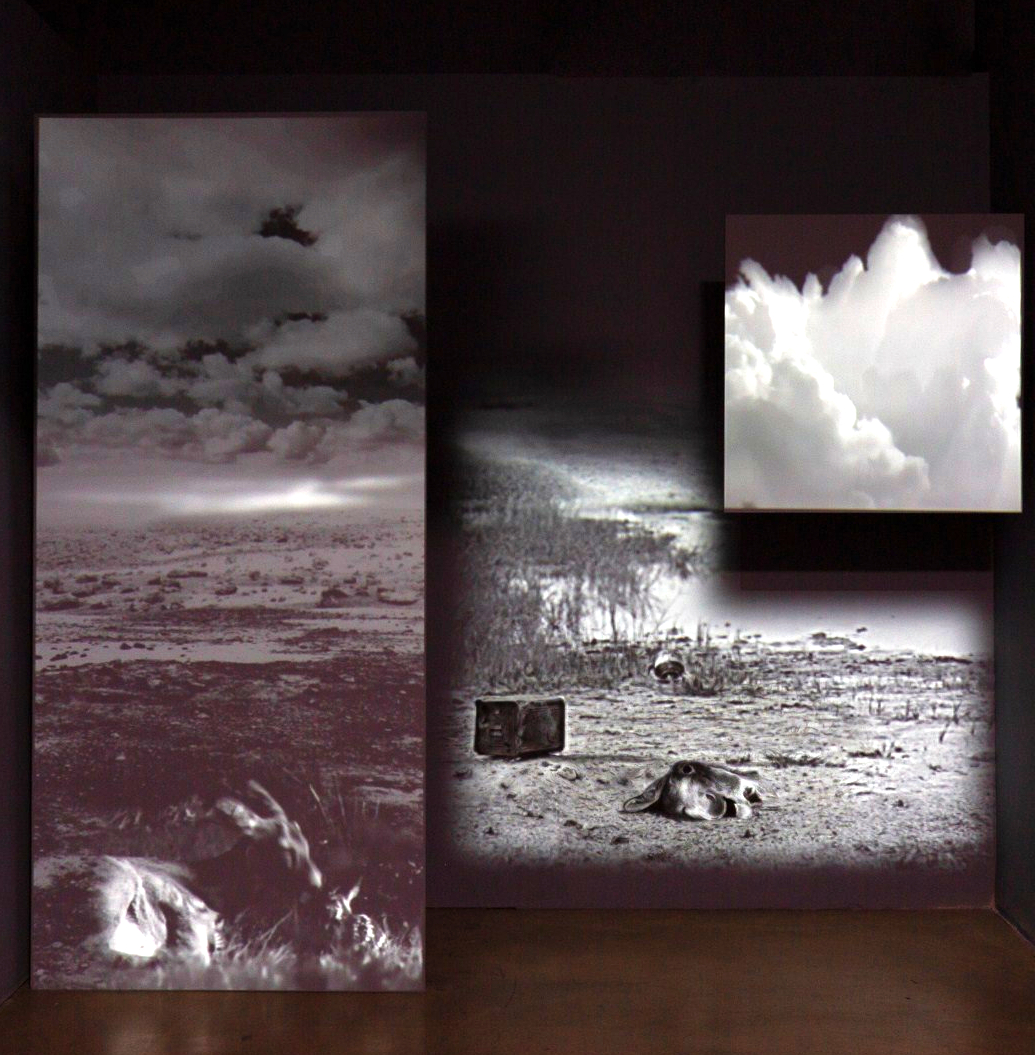

The Indian artist Ranbir Kaleka’s video installation is a pilgrimage through landscapes of desolation in which – accompanied by a sound track rich in volcanic seething, hooting trains and plangent elegies – we glimpse many catastrophes. Kaleka suggests we are as vulnerable as the species we have hunted into extinction, and our haunted pasts prefigure our threatened future. The Cuban-American artist Maria Magdalena Campos Pons revisits, through works that are immensely tender, elegiac yet redemptive, the sea as a membrane between perilous voyages and hazardous landfalls. She works at the shifting border between figuration and abstraction, gently pushing us into uncertainty. We cannot tell whether we are looking at driftwood or bodies washed ashore.

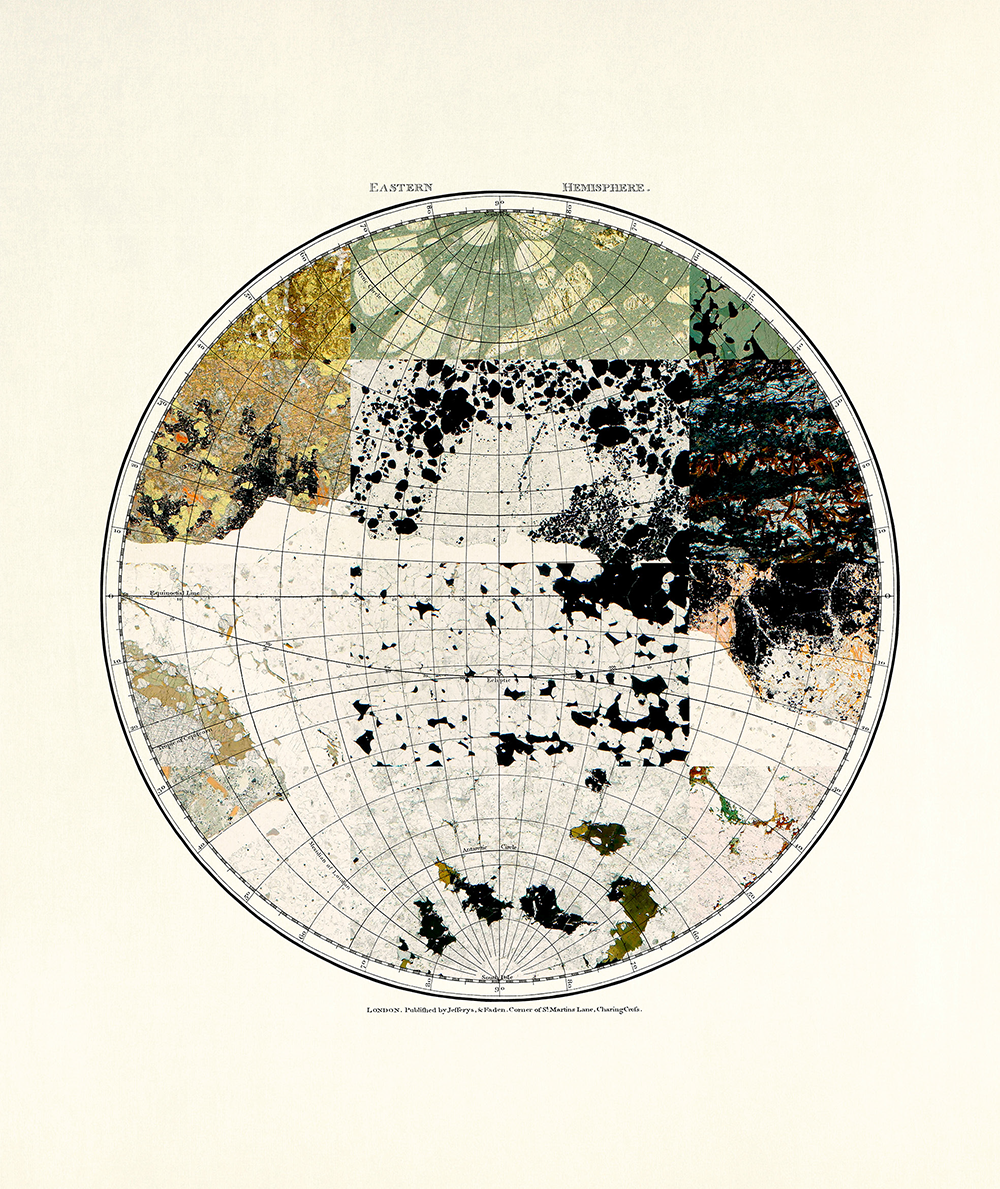

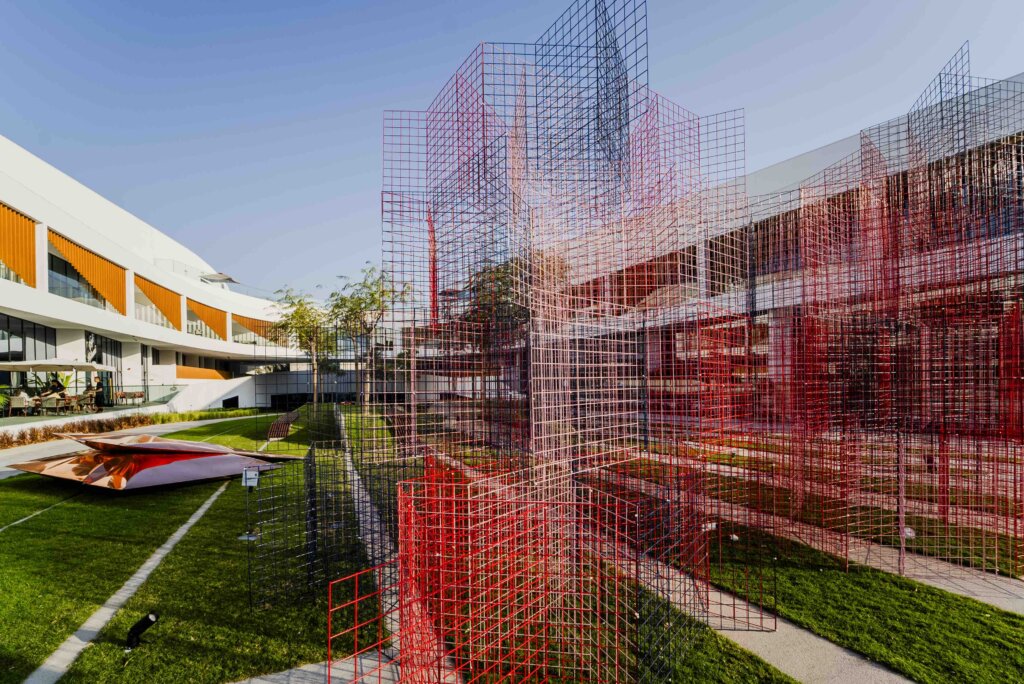

The Peruvian artist Elena Damiani bases her work on rigorous geological, edaphic and meteorological research, creating grids or atlases based on evidentiary material – views of the earth’s surface, evocations of weather activity – only to question the scientific unassailability of the mapping. Damiani’s poetics of drawing, collage and engraving unsettles the archive and evokes visions of impermanence. The Indian artist Tanya Goel combines a robust material engagement with a reflection on urban expansion. Goel’s seemingly abstract chromatic grids reference the modernist artist-pedagogue Josef Albers – her colours are, in fact, made from construction-site materials, powdered into pigment. Goel also exhibits architectural fragments, composing a portrait of contemporary Indian metropolitan processes of decay and recycling.

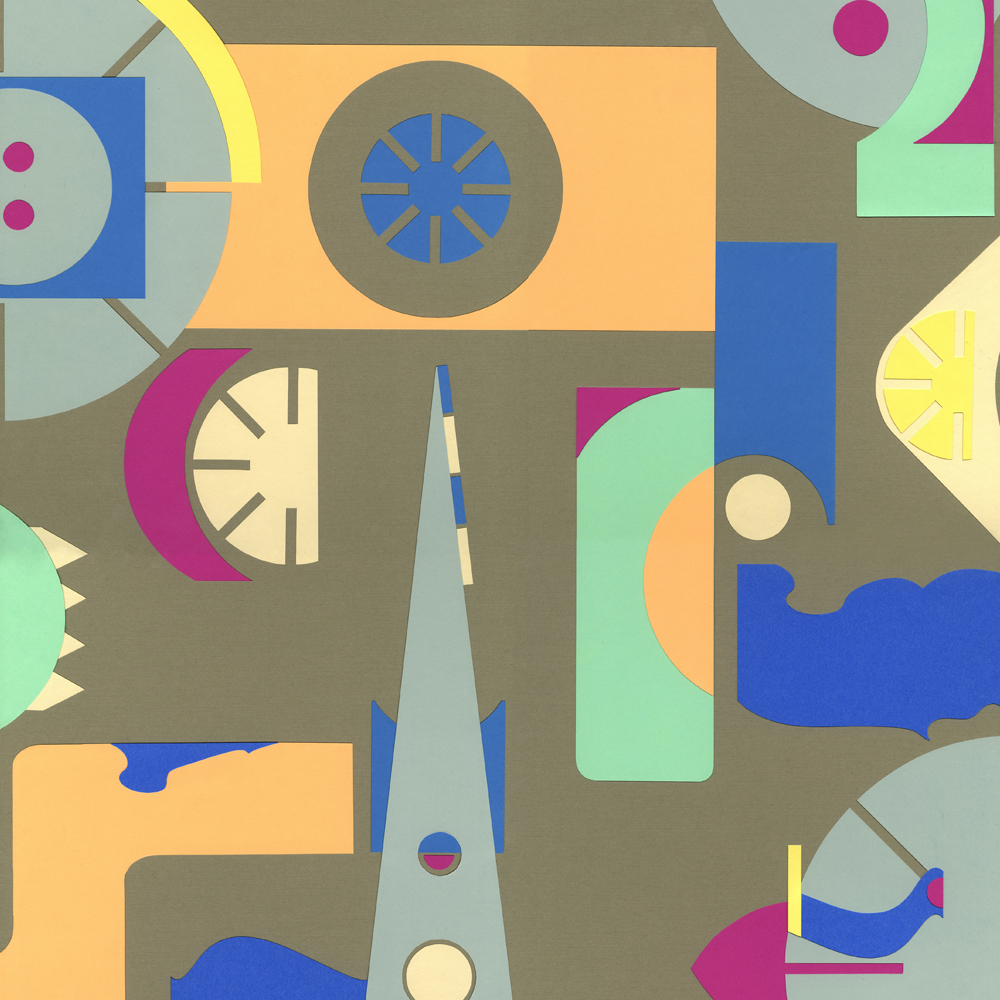

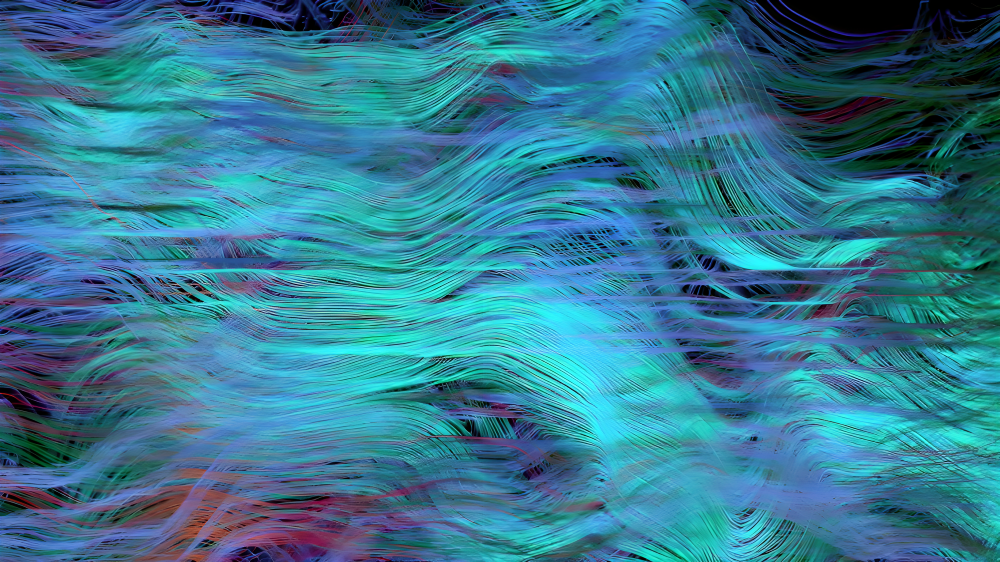

The Pakistani artist Adeela Suleman’s works carry us into a realm of what seem to be mediaeval histories or magical story cycles. Here, we encounter headless warriors and martial elephants. As we engage with these images, exquisite and fierce, we recognise them to be fables for a present in which warfare remains endemic across the world. The Yemeni-Bosnian-American artist Alia Ali’s artworks fuse photography, textile and wax print together to evoke archetypal figures and cosmic landscapes. At the same time she signals, through her materials and patterns, towards colonial histories of exploitation and migration. Through her optically stimulating strategy of camouflage, Ali merges figure, ground and pattern to challenge the viewing eye. The Japanese-born artist Yohei Yama creates large, immersive works based on the patterns in nature, evoking light, clouds, sand and currents. These works imply a cosmic scale and convey it through a sense of optical tremor, inviting viewers into a condition of rapture.

The Mexican artist Tania Candiani works at the confluence of linguistic and musical systems, often taking formal correspondence or analogy as her cue. Viewers will be surprised by a musical instrument Candiani has improvised from a Calicut string loom. This work, at the cusp between music and weaving, was made in a transcultural and collaborative manner by the artist with musicians from Mexico and Kerala. An interactive work, it invites viewers to play it. The Nepal-born artist Youdhisthir Maharjan creates works that are intimate in scale yet cosmic in tenor. Maharjan melds aleatory, chance-based techniques with the discoveries of a pensive literary imagination. He uses cutouts, shaped from the pages of books, and an array of sophisticated techniques, to suggest mandalas, star maps, and scores for voices in a universally distributed ensemble. In the Iranian-origin Moslem Khezri’s works, the focus is the classroom, an unlikely theatre in which the act of reading is a powerful, if understated, political statement. Khezri’s protagonists revisit social visions and review the trajectory of history. In each work, an illumination picks out one or another figure. We think of Rembrandt’s group portraiture, and also of Noor, the light of divine grace.