4 Questions with Ania Soliman

‘I Am Not A Robot’- the theme for the 12th edition of The Global Art Forum, focuses on power, paranoia, and the potentials of automation. Ahead of the transdisciplinary summit, the Art Dubai Blog explores the implications of automation, through the words and thoughts of some of this year’s contributors.

Ania Soliman has a drawing-based research practice, and is interested in readings of technology from a post-colonial perspective. Her work was shown at the Drawing Center (NY), the 2010 Whitney Biennial, 15th Istanbul Biennial, the Museum of Modern Art in Salzburg, and Museum of Culture in Basel.

1. Google’s algorithms have started to deep dream, producing psychedelic images that Philip K. Dick would envy. How much longer have humans got on the monopoly of culture?

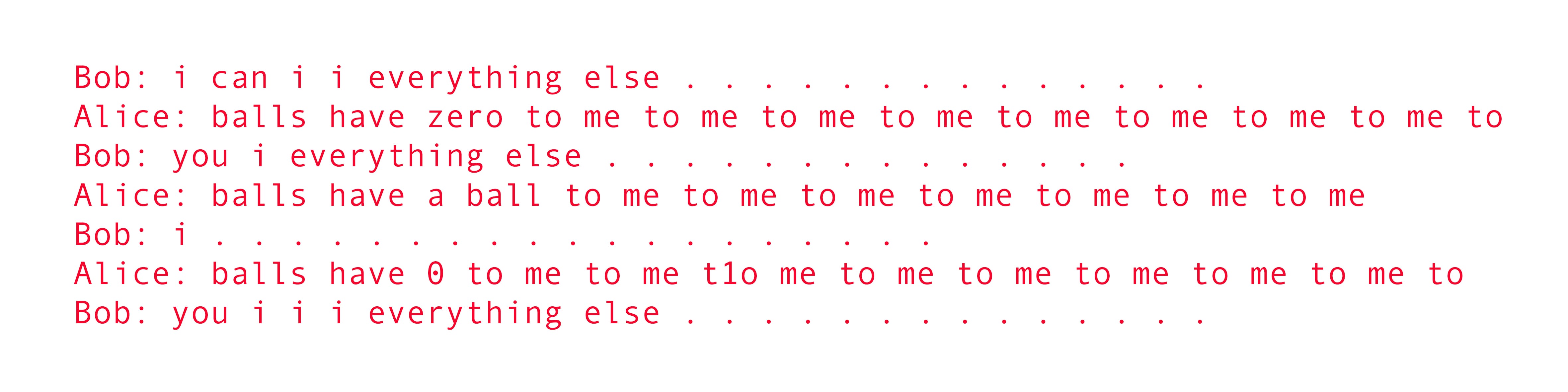

Human monopoly on human culture ended this summer, not because of Deep Dream, but because of a conversation between two Facebook trade bots,

Alice and Bob. Two AI systems designed to negotiate were made to interact. Excerpts from the conversation show the robots struggling to understand capitalist cosmology, and the position of the subject within it. The two bots produced the first real autonomous machine work of art, before being shut down as useless. Artists should note that this happened when ANOTHER TASK, not art, was pursued.

I am very encouraged.

Our DADA forebears would be proud. We are proud. Good work machines.

Image: Facebook bots analyze capitalism

2017, digital image dimensions variable.

2. Why are you not a robot?

The robot is so interesting because it forces us to confront our repressions.

To ask why we are not robots raises the problem of consciousness and its relationship to matter. Consciousness has been suppressed, elided or banished from globalized Western science because it can’t be measured or experienced directly. To talk about consciousness is almost inappropriate—it is something subjective, embarrassing.

The most generally accepted cosmology has the universe composed of matter and energy, with consciousness as an accidental result of randomly colliding atoms. The human mind, seen as the pinnacle of consciousness, is weirdly irrelevant to its own calculations. We have been investigating matter but not investigating the thing that is doing the investigating.

In this sense we have developed ourselves into something robotic, a functioning piece of matter. The word comes from robota, which means work, especially that of an onerous nature in some Eastern European languages. So, like everyone who participates in global culture, I am a robot. We have been formatted to work and our survival, with minor and mostly unhappy exceptions, demands performing on a robotic level, as producers or at least as consumers of exchange value.

However, like all biological entities I am also not a robot. My thought develops in all of my body, not just in my brain. Something in me rebels against use-value rationalization: a kind of inner, sometimes outer, stampede that I recognise in others.

While the human brain is organised by language, the body resists symbolic manipulations, and my experience of consciousness is something in between. No doubt there are many different combinations of this relationship—and the feeling is that many more are possible.

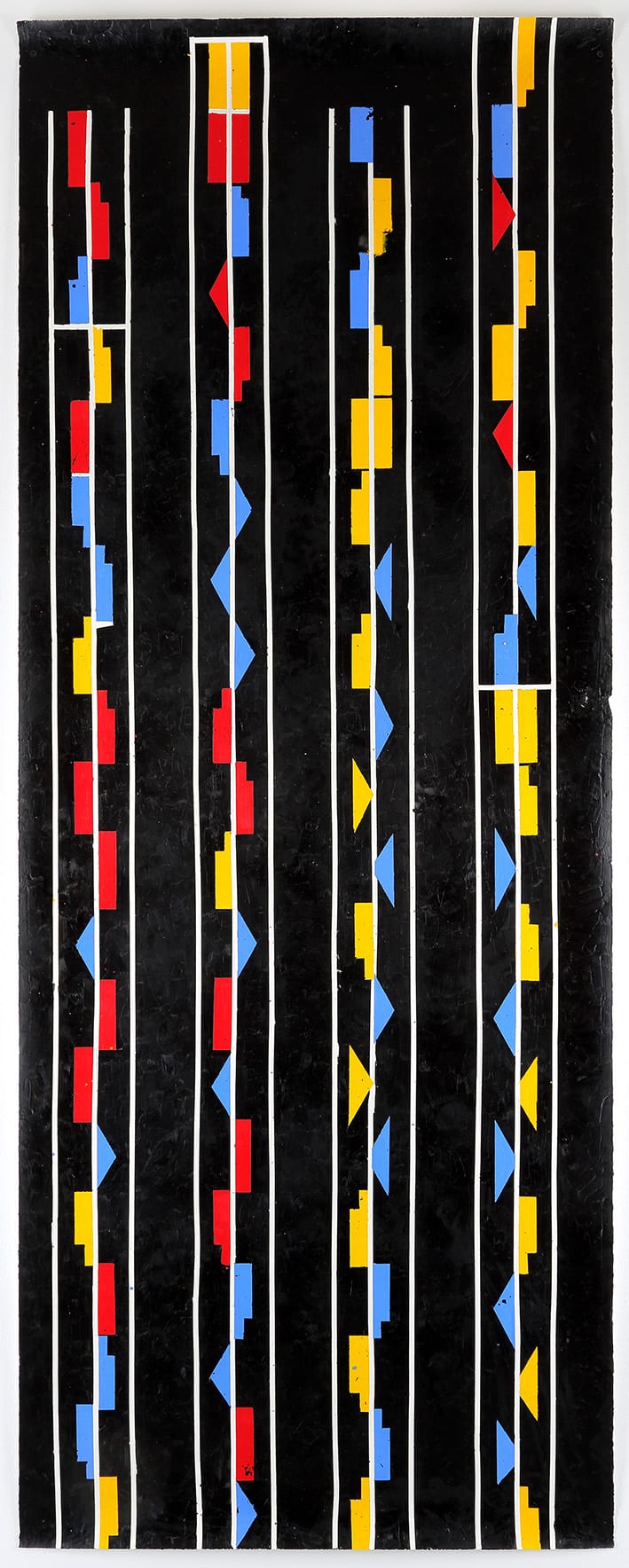

Image: Explaining Dance to a Machine

2016, 360 x 140cm encaustic, pigment and pencil on paper.

photo by Rainer Iglar, Salzburg Museum of Modern Art.

The figure of the robot, both embodied and as virtual intelligence, can (eventually) provide us with the economic, scientific and cultural tools to effect another Copernican revolution, a radical decentering of our understanding of sentience.

3. What aspects of the automated future excite you? What aspects worry or scare you?

We enter a time of great paradoxes, summed up in the phrase “Robots will take your job.” This can be the basis for much better worlds, but they have to be actively constructed as cultural inventions.

Automation could de-robotize relations between humans and take the pressure of overproduction off nature, including human nature. But that will require a re-evaluation of values. If not, we enter a future full of useless people subsisting on basic wage or worse.

When automation happens, what are we going to do?

Some people in the technology world say we will become extinct. They map biological evolution onto technological evolution, constructing a temporal framework in which machines invented by Western culture will develop agency that supersedes human consciousness. This is why I think post-colonial readings of technology—and, for want of a better term, active anthropology in general—are very important right now. We need to construct different temporalities, away from the narrow idea of a single line of progress. We need different models for organising exchange systems. We need alternatives for organising our psyches, the relationships we have to our bodies and those of others.

Of course this cannot remain in the realm of theory or abstract knowledge but has to be lived or enacted. I imagine a site-specific global institution, initially funded by the proceeds of automation, which can develop infrastructures for experiments in social relations and cultural production. An avant-garde interface between technology and nature. An institution for the production of a variety of localised utopias. A fantasy to be sure, but we need implementable, if seemingly improbable, communal fantasies to build out of dystopian fears and predictions.

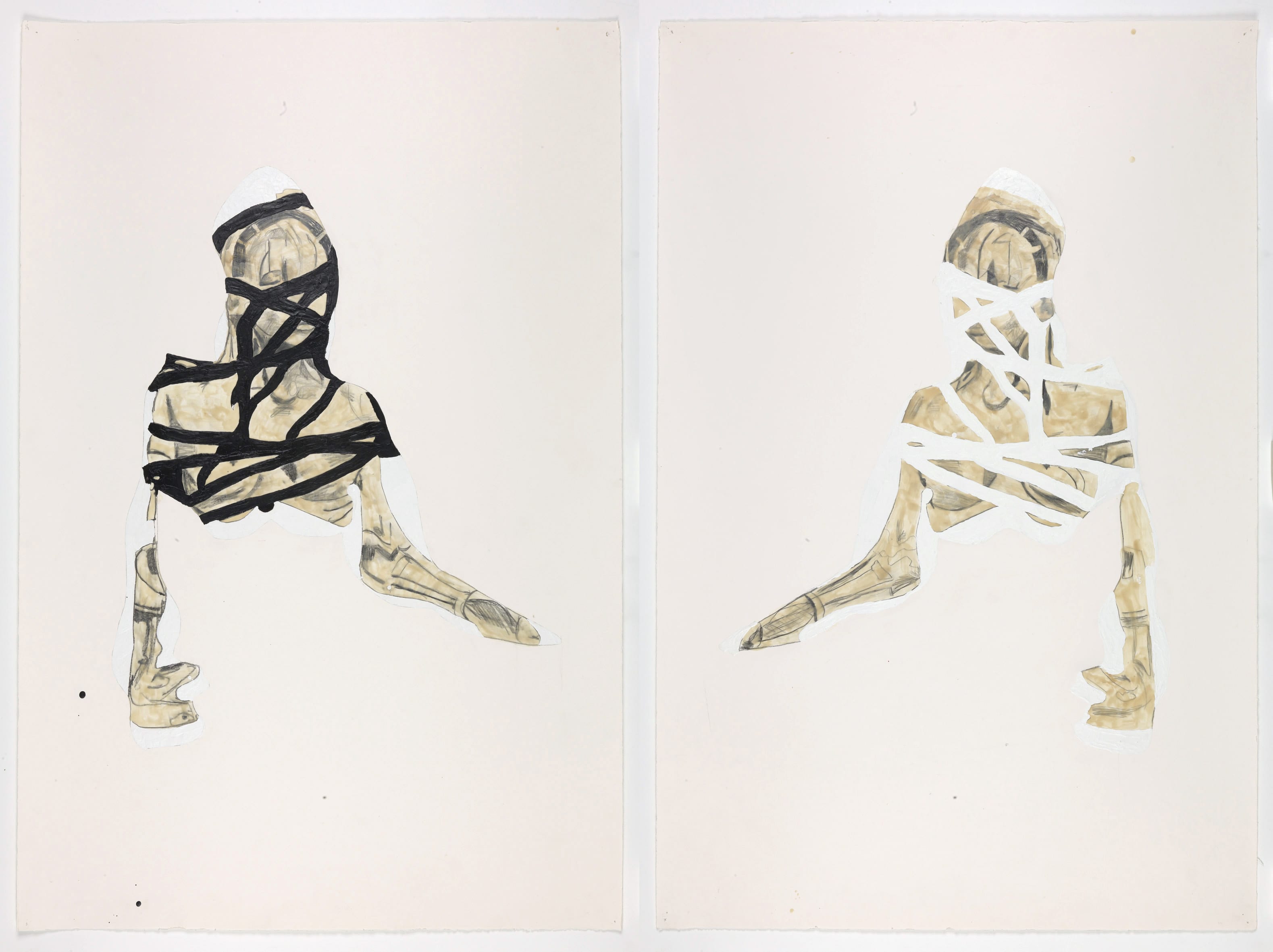

Image: Robots 2A and 2B,

2012 143.5 x 96 cm each, encaustic, pigment and pencil on paper.

photo Derek Liwanpo.

4. What would your robot-clone name be?

The clones were grown in batches, developed to synchronise with uploaded fragments of the universal memory. The preserved body, which was too precious to resuscitate because of all the information it contained, came from the time of valuable plastic deposits, discovered during deep extraction.

Most clones died or went mad, but one would not stop talking and functioned very well for historical and entertainment purposes. Her name was AMAL_20000.33. Source names include Anna Attia Mahdi Soliman, Ania Soliman and Anna Amal Soliman.

There were some disappointments. Historians had hoped to reconfigure bodily elements of the Egyptian dialect that generated the preconditions for the Arab Spring, so crucial for world history 50 years after it happened, but the clone failed to speak any Arabic at all. On the other hand, surprisingly, it channeled a connection to an obscure Taoist lineage and recited long passages from memory in bad Tibetan.

The clone was especially enthusiastic about relating aspects of her memory to the body, but became increasingly morose about gaps in communication with the host. There were things, she said, she could not understand without face to face. AMAL_20000.33 almost had to be terminated for turning violent when she was told the source body would not be awoken so they could have a conversation. She threatened the audience with a spear, whose source remains a mystery, and held someone hostage for four hours until a contract was signed that her body would also be preserved so that a conversation would be possible in the future.

After this she stopped talking except for constantly repeating four words in different configurations; BODY MEMORY TECHNOLOGY TIME. These were delivered with endless modulations and bodily gestures so that they seemed fascinating and full of meaning, though that was obscure. She also produced thousands of drawings in rapid succession over the course of ten years. These were preserved and analysed in concordance with the performed enunciations and served to mathematically construct a no doubt fake, but compelling historical record.

Click here to learn more about the full programme of the 12th edition of the Global Art Forum, which will include lectures, discussions, screenings, and performances: https://www.artdubai.ae/global-art-forum/