‘Rewind’ is a feature series on the Art Dubai blog, looking at the life and personality of a Modern artist from the Middle East, Africa or South Asia, who is connected to the fair through one of the Art Dubai Modern participating galleries. The stories are told through the eyes of a close relative.

by Myrna Ayad

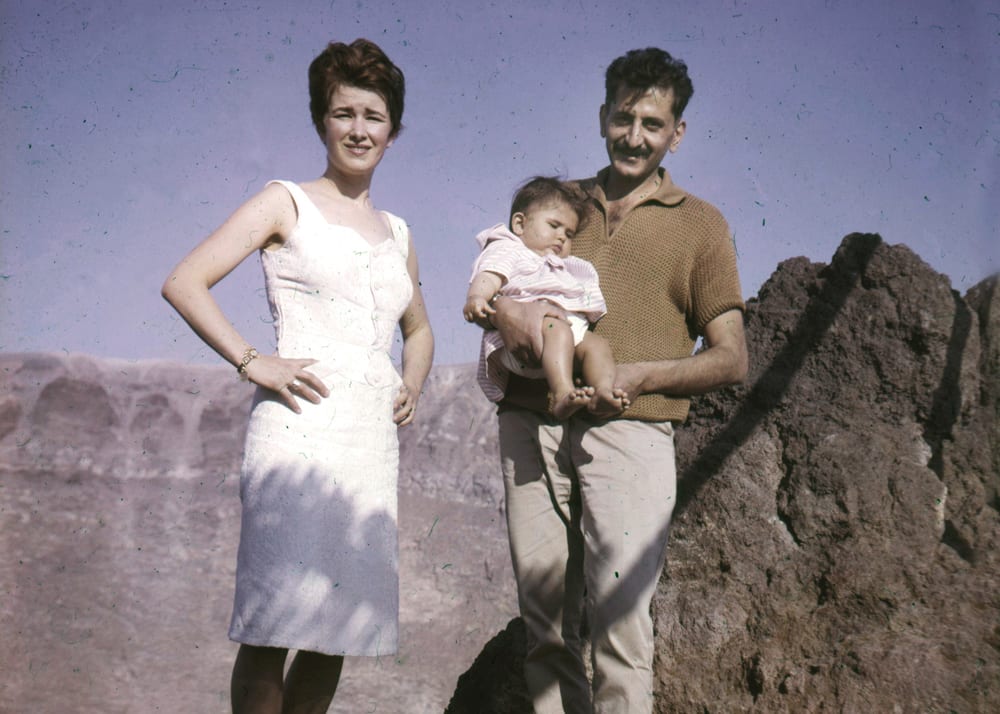

Nicole, Shafic, and Christine, 1962.

When I was little, I was often in my father’s studio painting on one side and he on the other. It was a sort of ‘collaboration’. He was there but he wasn’t there, and there are things that I remember – there was a special way he painted, things that happen only at the moment of creation; the way he moved in the studio, how his body appeared differently in the studio compared to elsewhere. I saw my father in terrible states because he did not want to sell a painting. The relationship between the artist and his work is special; it’s a part of themselves.

My parents had a difficult relationship and life later became complicated. He was often away; physically, but in his mind also. He was absent and really absorbed by his work. My father was very affectionate, but would suddenly become distracted and that was the most difficult part to understand as a kid. I would always find him in his studio, but it was hard for me to find my father as a parent there.

I think he loved Lebanon in its complexity; he absolutely needed to go and absolutely needed to leave and absolutely needed to continue to see his friends and absolutely needed to be elsewhere. I think that leaving Lebanon for France and operating between two countries and two cultures had an effect on him. There was a ‘double belonging’. I don’t think he needed things to be easier, I think he needed things to be difficult because he had a complicated personality. He was very affected by the war in Lebanon, but he went back often, though not for long stretches. He stayed in contact with many people to remain inspired and to keep the memory of his childhood alive. It was absolutely essential. But at the same time, he never wanted to go back to live there. This was someone in contradiction, in a constant state of duality.

I summered in Lebanon as a child and that was rather difficult. I did not understand what happened with the war, so it became a painful country for me. I still visit, but I cannot stay long, there is a repellent energy and a little despair sometimes. I feel good one moment and then afterwards, it’s a bit like my father felt – I need to leave quickly. I guess I take a little bit of him in that respect.

I did not realise how essential Lebanon was to him because I always saw him working and exhibiting in France. It was only later when I read his notebooks that I discovered how much Lebanon was an absolute foundation to which he returns constantly, especially his paintings from the 1980s.

Towards the end of his life, he asked me to manage his studio. I couldn’t because I had a baby and felt that I did not have the skills to handle his work. I had the impression that the studio was a mess, but in fact, he had organised everything as though he was planning for the future, as though he wanted his work to go on. He had kept tons of archives on his exhibitions, classified files, letters, personal collections…I found it highly impressive, as though he was transmitting something, the demand for a legacy. I was fascinated and felt a responsibility. I discovered new aspects of my father’s personality and that explains things even

Shafic and Christine at the studio in Montsouris, Paris, 1965.

Christine, 1964. Tempera on canvas on cardboard, 17×19 cm.

about me. These discoveries gratify the parent-child relationship.

Enfantine. 1964. Oil on canvas, 100×100 cm. Courtesy of Sursock Museum.

At the Studio. 1967. Oil on canvas, 100×100 cm. Courtesy of Shafic Abboud Estate.

Image de Juillet. 1970. Oil on canvas, 130×130 cm. Courtesy of Shafic Abboud Estate.

Because he left a lot of records and because I have done a lot of research on his work, I now better understand who he was. I feel reconciled with him, not that I was angry, but I see it all differently now. When I read his notebooks, I have a clearer understanding of the moments when things were difficult for him, moments in retreat, moments of torment, moments of fragility. I better understand the whole flow of his life and his questions, things that I had not perceived before.

My father fought hard to be recognised and I would very much like academic work done on his work. I would like younger generations, students and researchers to take it a little further and provide new readings. I would like the Arab world to explore his work more seriously, by way of national collections and exhibitions. My father’s work has to be seen and shown. These are the ideas that I have and I hope not to betray him or his legacy. He was very intellectual and never gave up searching. That was his way of living. I see the precision he had on some things and I think that is the lesson I learn from him – to be meticulous in certain disciplines, to be accomplished and to remain curious.

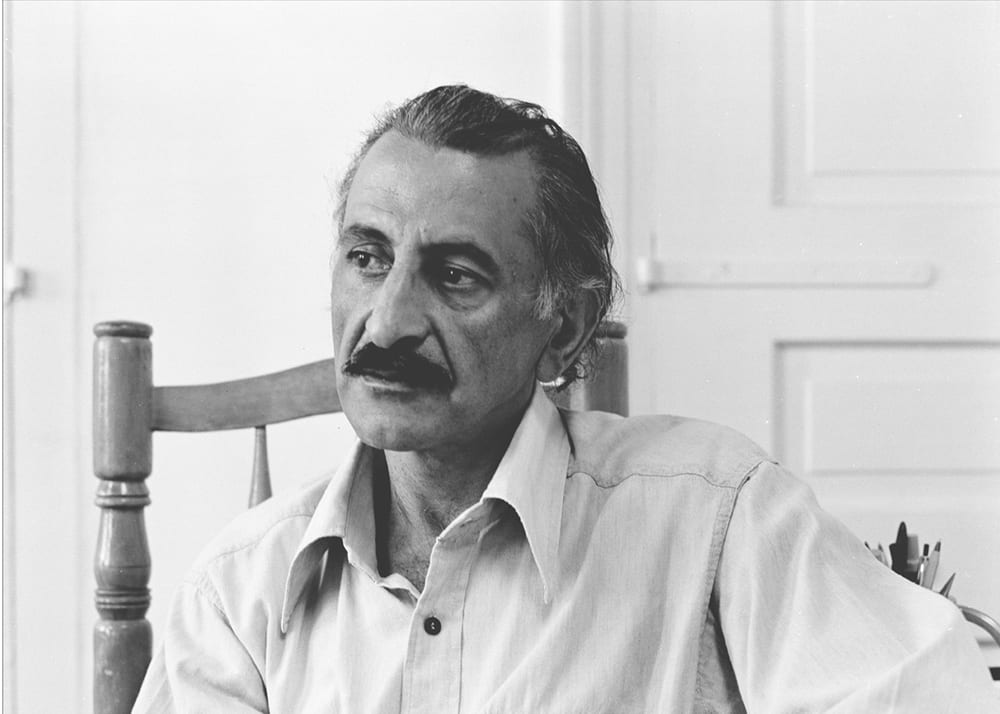

Shafic Abboud. 1972. Photo by Waddah Faris

Images provided by Christine Abboud.