‘Rewind’ is a feature series on the Art Dubai blog, looking at the life and personality of a Modern artist from the Middle East, Africa or South Asia, who is connected to the fair through one of the Art Dubai Modern participating galleries. The stories are told through the eyes of a close relative.

Tasveer Shemza talks about life with her father, Anwar Jalal Shemza.

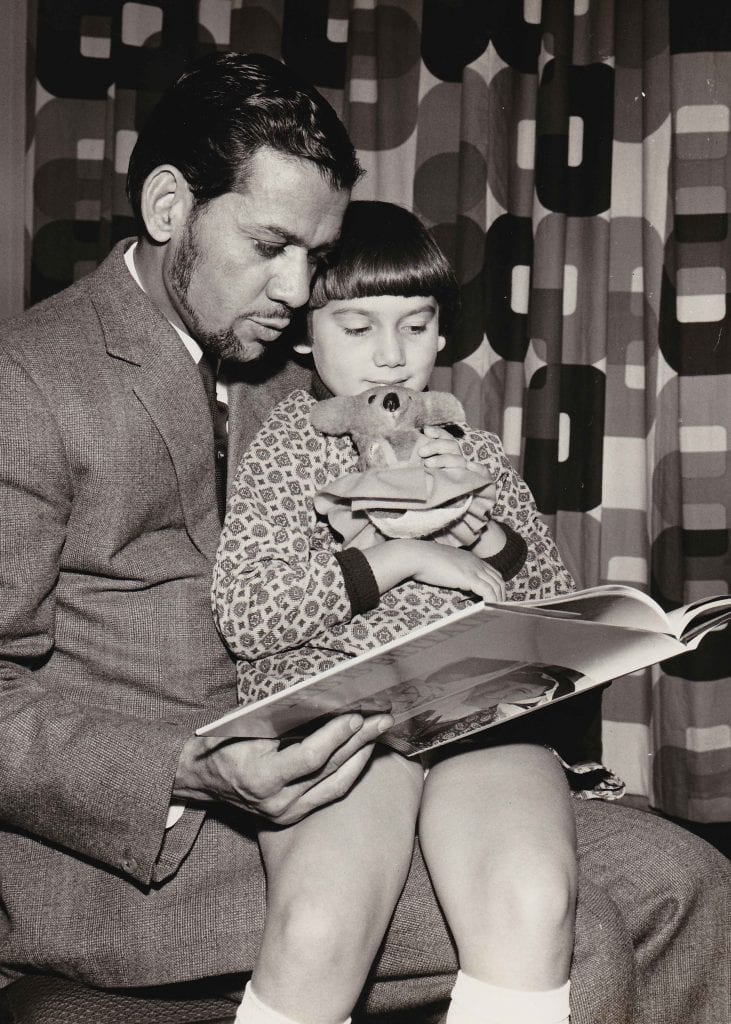

Although I’m not an artist, I had my 15 minutes of fame in 1966, when I was six years old and won a Blue Peter competition for the first Royal Mail Christmas stamp in the UK. Because my parents were artists, I had access to the most beautiful materials and created an ink painting. The theme was of the three kings, but it was actually a portrait of my father, Anwar Jalal Shemza.

Recently, I have been looking back at my parents’ lives and I think the dice just didn’t fall right for them with circumstances and decisions that they made. They were students when they met at an art ball in London in the late 1950s; it was fancy dress and my father wore his Pakistani national costume and my mother a painting smock. I think they were instantly attracted. He was at the Slade and she at the Institute of Education. Though he was known in the Lahore Art Circle and was a successful artist in Pakistan, once at the Slade, he suffered a crisis in his practice. He questioned what he was doing, and needed to find a new beginning. He wasn’t content to imitate Western art and found inspiration in the British Museum.

Tasveer Shemza’s ‘Three Kings’ themed stamp, 1966.

Anwar Jalal Shemza and Tasveer.

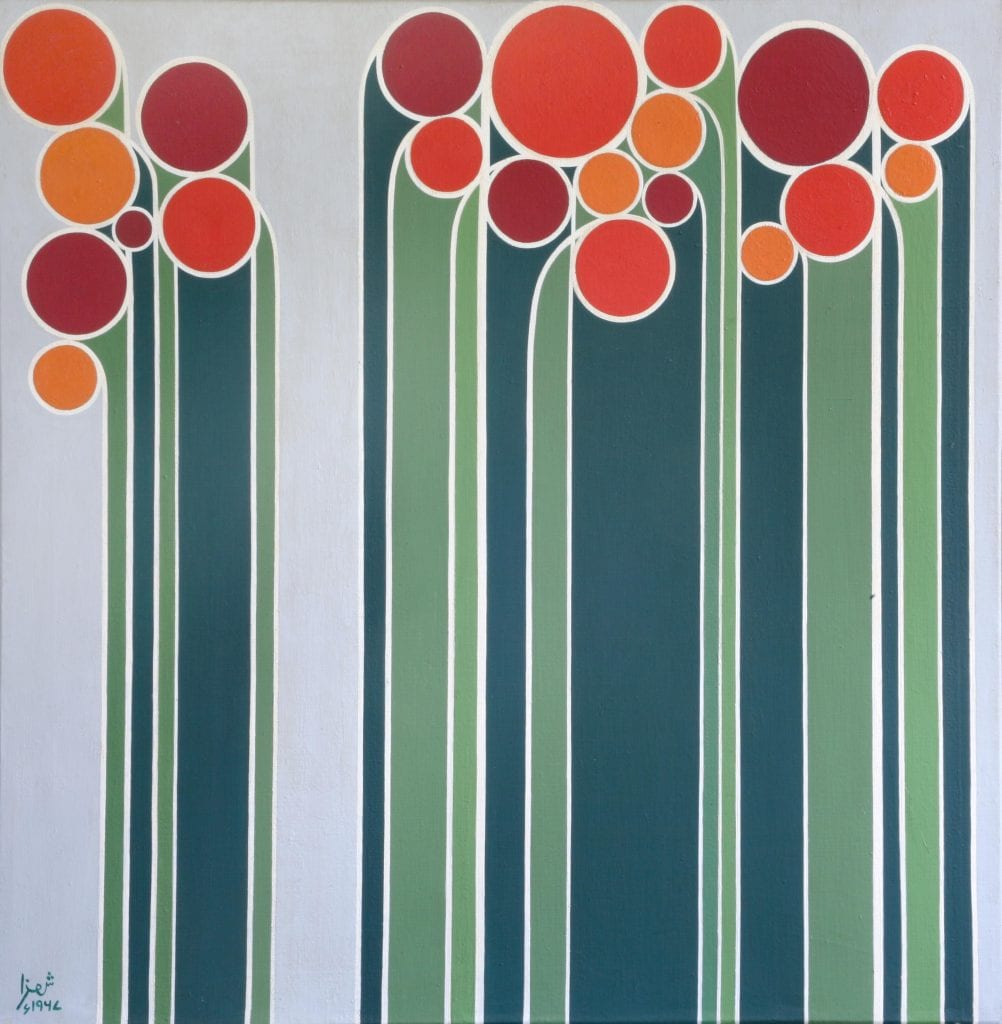

As an exile, my father rediscovered his heritage to create a unique style and had shows at Gallery One and the New Vision Centre. He was doing well and intended to take his knowledge and family (I was a baby) back to Pakistan, work as an educator at his alma mater, the Mayo School of Art in Lahore. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen, so my parents went back to the UK in 1962 and settled in Stafford, my mother’s hometown. Both worked fulltime as art teachers, and my mother supported my father, managing the household as he continued his practice. She put her own painting on hold, feeling fulfilled by his work, but her work started going back on the walls after he died. It was a mixed marriage in many ways, not least religion, but I had the sense that my parents had a strong sense of faith and that translated into really strong moral values and ethics for me.

In his lifetime, my father worked in relative obscurity and that was not the way he wanted to end up. There was little recognition and he must have had such a strong sense of belief in his practice. I strongly felt that his work was really exceptional and I’d never seen anything like it. I still think that is the case. I was so proud of it and always thought it was amazing.

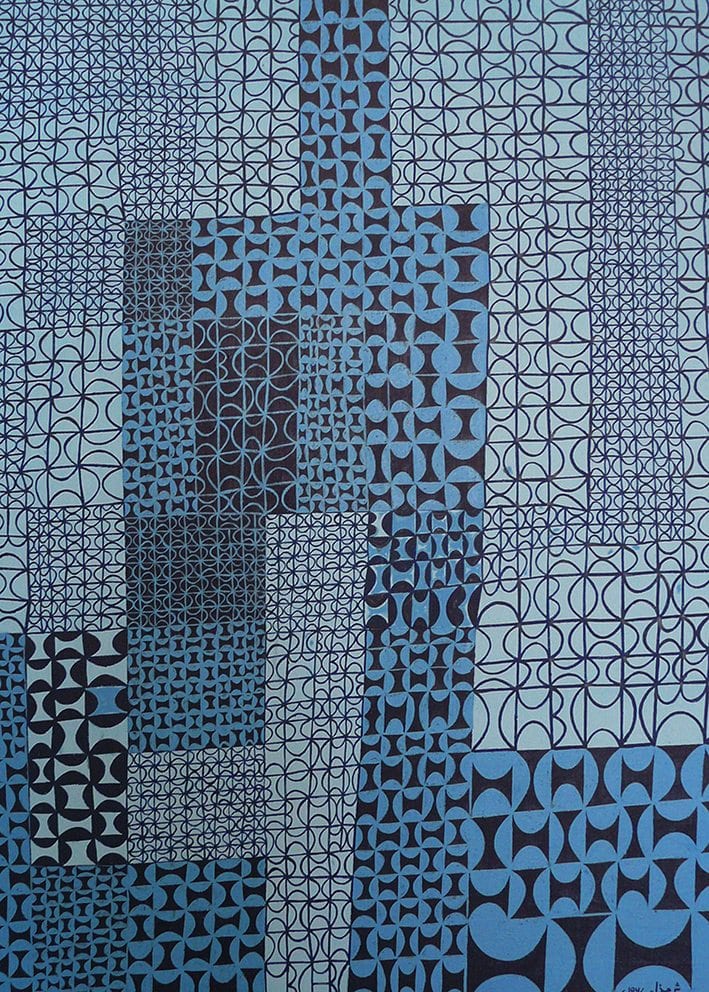

I believe Islam was deeply entrenched in him and he had a spiritual side. I think his work had a lot to do with his background and culture; that’s probably where he sublimated his desires. I think he took the architecture, vibrant colour palettes, landscapes, city-scapes, palaces, calligraphy, all of that, and some of it became lyrical. There is a longing. It did become a private reverie.

I watched him work; it was either at the dining table or during the summer, in a studio at the bottom of the garden. It was constant. We have a fantastic collection of sketch books, and works from there would be selected to be painted. He was a fantastic teacher and loved his job; he wasn’t doing it because he had to. Though we lived about 30 minutes away by car, his students would visit him to see his work. I know they were very inspired by him and today, some are family friends, who have forged artistic careers on their own. I doubt they would have done that without my father.

I do know that my father would not have got his job had it not been for someone who overrode the prejudices in the 1960s; his application was initially rejected, but the head of department was impressed with his experience and convinced the principal. Nobody was Pakistani in my town, but there was prejudice at the time. I think it must have been a constant battle for him. I wish I had been taught Urdu and felt more of a cultural influence from his side, I was always very grateful for having a strange name, because it gave me a reason to explain my origins.

A lot of my childhood and teenage years were a rebellion towards my father. I didn’t become an artist, because there was too much of it at home. I think part of my rebellion stems from the fact that I didn’t want something as intense as that and he was constantly intense. I saw the difficulty in art and in life. I never had a resolution with him and there are so many questions I’d like to ask. He died in 1985; he was 56, but he looked much older. He’d had a heart attack when I was 16 and he knew that he should relax more, because really it was stress. It was the intensity with which he lived, teaching all day and working on his practice all night and that’s why he died so young.

As my mother got older, she felt responsible for his work. In 2004, she staged a show in Pakistan and also exhibited some of her work. Out of that, Hammad Nasar then-Director of Green Cardamom Gallery in London contacted her. Shortly after, Dr Iftikhar Dadi became interested in Shemza’s work and began to write and give presentations about him and we are currently working with Jhaveri Contemporary. A number of pieces have been sold to institutions like the Tate, the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Guggenheim, to name but a few, and there has been more exposure and wider recognition of his work. We also had a spotlight room display at Tate Britain in 2015-2016 and published a monograph to coincide with that. This month, The Whitworth at the University of Manchester stages an exhibition of works by South Asian modernists and Shemza’s work will be included. My mother has just turned 80, and I feel a greater responsibility. Our rationale is sharing the work, getting that recognition and getting it written into art history.

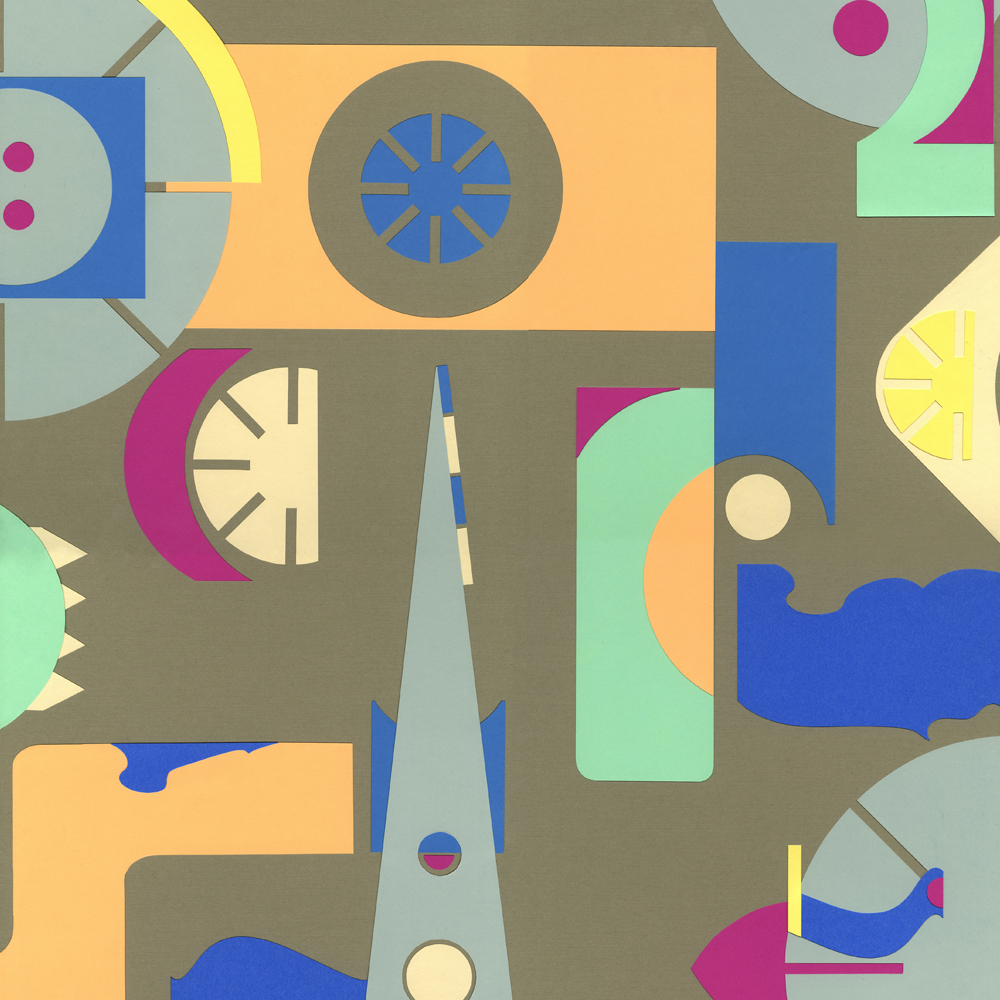

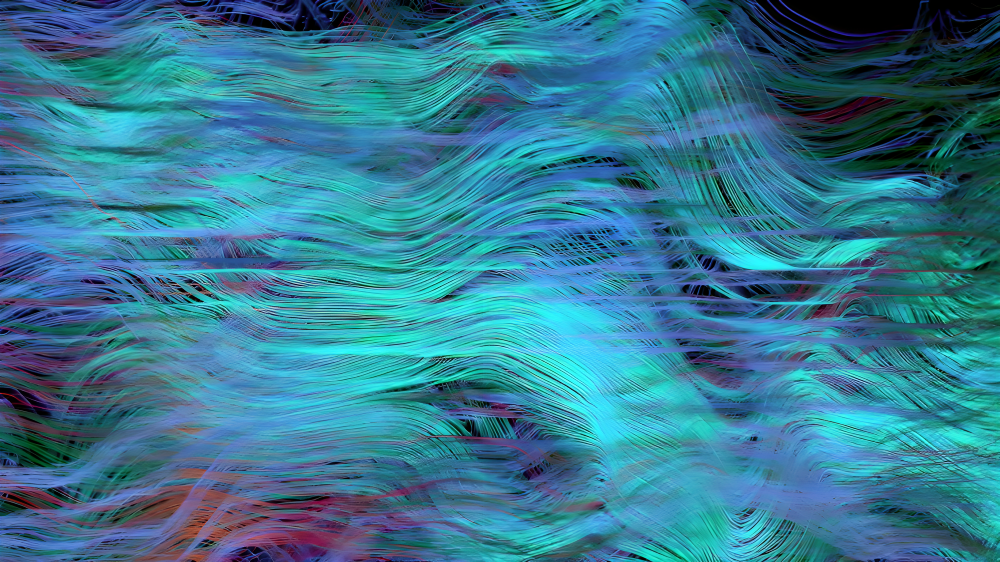

The Apple Tree, 1962

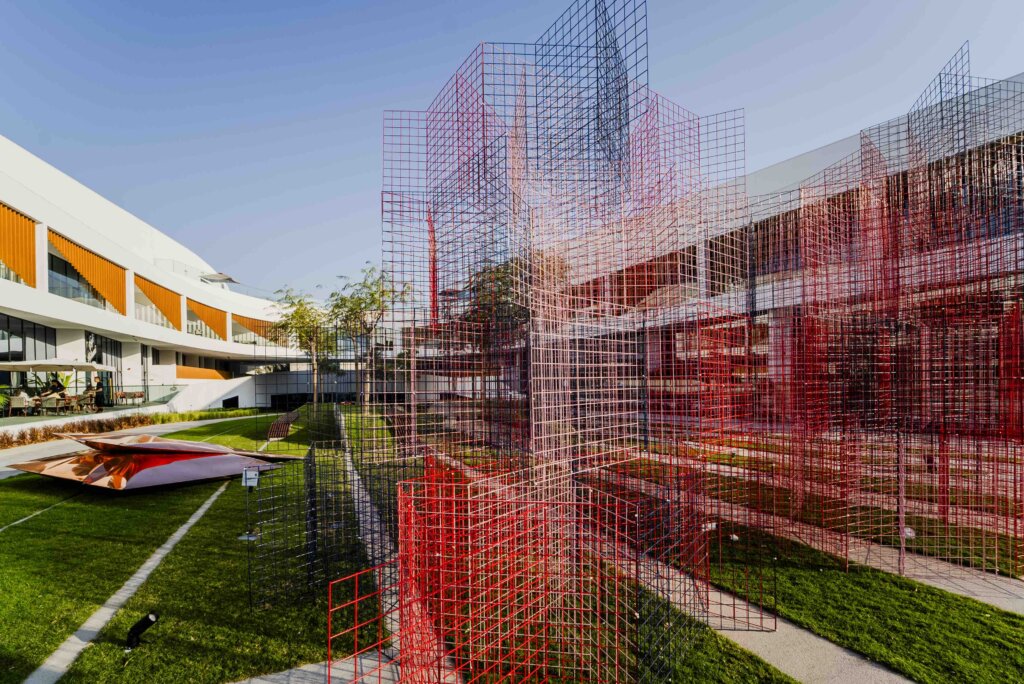

Anwar Jalal Shemza painting ‘The Red House’ in his studios, 1960

Blue Blue Jazz, 1967

I have the most incredible reminder of my father’s work – a lively piece from the Meem series. I had it on my wedding cake and for my 50th birthday had it made into stained glass for my front door. I have pieces I won’t give away, they’re the ones I grew up with. I do feel possessive about all of them, but I do want them to be shared and seen. He would have liked that.

Meem One, 1967

All images courtesy of the Estate of Anwar Jalal Shemza.